There is no question that the coast of Maine is a treasure chest full of delights for the cruising sailor. Cruisers come from all over the world to experience the unique variety and quality of this coast. There are also some unique challenges along the coast, but with a bit of care and planning the totality of the adventure is unmatched and unforgettable.

Navigating the Rocky Coastline

Deep water is abundant on the Maine Coast, and what obstructions there are are well marked, charted and quite obvious. Just like driving down an interstate highway, it’s all pretty straightforward if you pay attention.

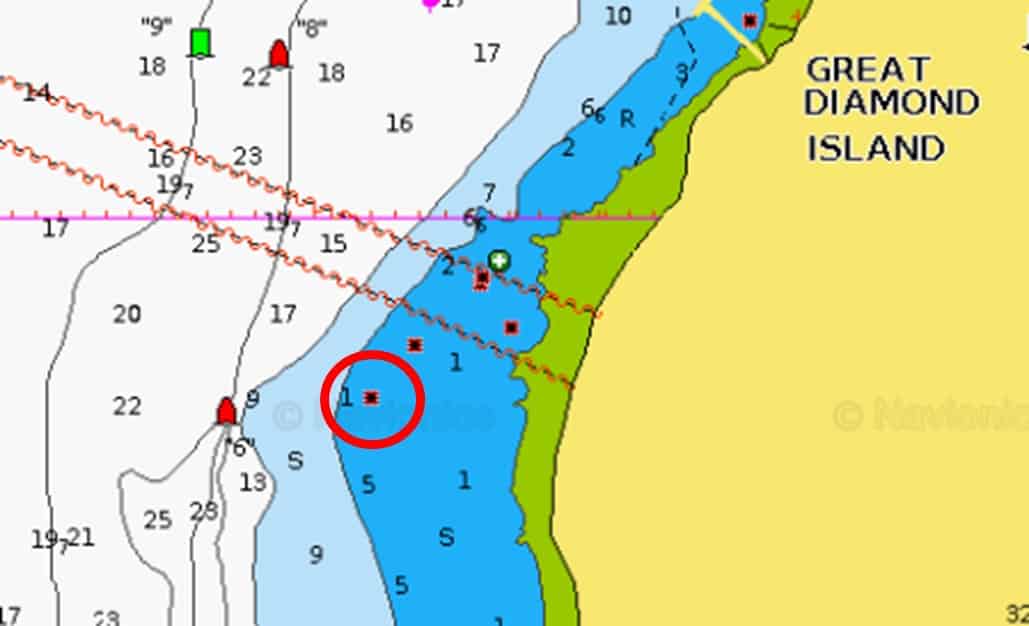

Pictured here is a beautiful Oyster 58 that had just completed a winter refit and was two miles from the marina on a short shakedown when she fetched up on a well-marked ledge west of Great Diamond Island in Casco Bay. This was in an area of excellent visibility, minimal current and 10-15 knot breezes. And yet, this is not an unusual sight along the Maine Coast. Why?

Well, clearly, no one on board was paying attention to where they were. I would venture to guess that not paying attention explains 95% of groundings with the other 5% explained by, “I thought I would have enough water.” Unlike sailing in the Caribbean or the Keys, where you can see the mostly sandy bottom 20+ feet down, the water in Maine is opaque and the bottom often rocky. By the time you can see the bottom, you are on it. So, how do you avoid ending up like the Oyster 58?

- Plan your route for the day before you weigh anchor. Make sure that the route does not take you through waters too shallow for your vessel or over isolated ledges amid otherwise deep water. Opt for a longer route if by so doing you can avoid a particularly tricky passage. Use of an auto-routing function is a good way to plan a route. Be sure that your boat’s draft is available to the program and always check the route closely before embarking.

- Have someone who is capable of monitoring your chartplotter and maneuvering your vessel at the helm at all times. Taking an occasional break from the helm will help you maintain vigilance when it matters.

- Monitor your location frequently by referencing your chartplotter and by visual reference to the surroundings, i.e., government marks, lighthouses, islands, points of land, ledge outcroppings or anything that can be cross-referenced between your chartplotter and what you are seeing. The amount of attention you must put into this depends very much on your surroundings, of course, but even in relatively open waters an occasional glance at the chartplotter to ensure that you are headed at your next waypoint is important.

- Use the CCA Cruising Guide for tips about entering or leaving particular harbors or anchorages.

- Follow other vessels of similar draft through tricky passages but continue to monitor your chartplotter while doing so and stay safely back so that should the vessel ahead make an abrupt stop you can stop before you get into the same trouble.

- Be aware of the tides. Chart depths are shown at Mean Low Water, which means you will have greater depths as the tide rises and also that you can have lesser depths in a low tide that exceeds the mean low. When in a shallow passage, slow down and monitor your depth sounder. In some cases, it may also be advisable to have someone on the bow watching for the bottom.

- Know your boat’s draft (i.e., the depth of its lowest part, usually the bottom of the keel, a deployed centerboard or propellers or a rudder on a powerboat). Second, you should be aware of the offset calibration on your depth sounder (i.e., are you measuring from the surface, from the instrument or from the bottom of the keel).

- Always remain vigilant.

An additional Navigation Challenge

If you are making your way up one of Maine’s rivers, the “red right returning” rule for passing navigational aids works. For much of Maine’s craggy coast, it is best not to assume whether you are coming or going. Let me show you an example.

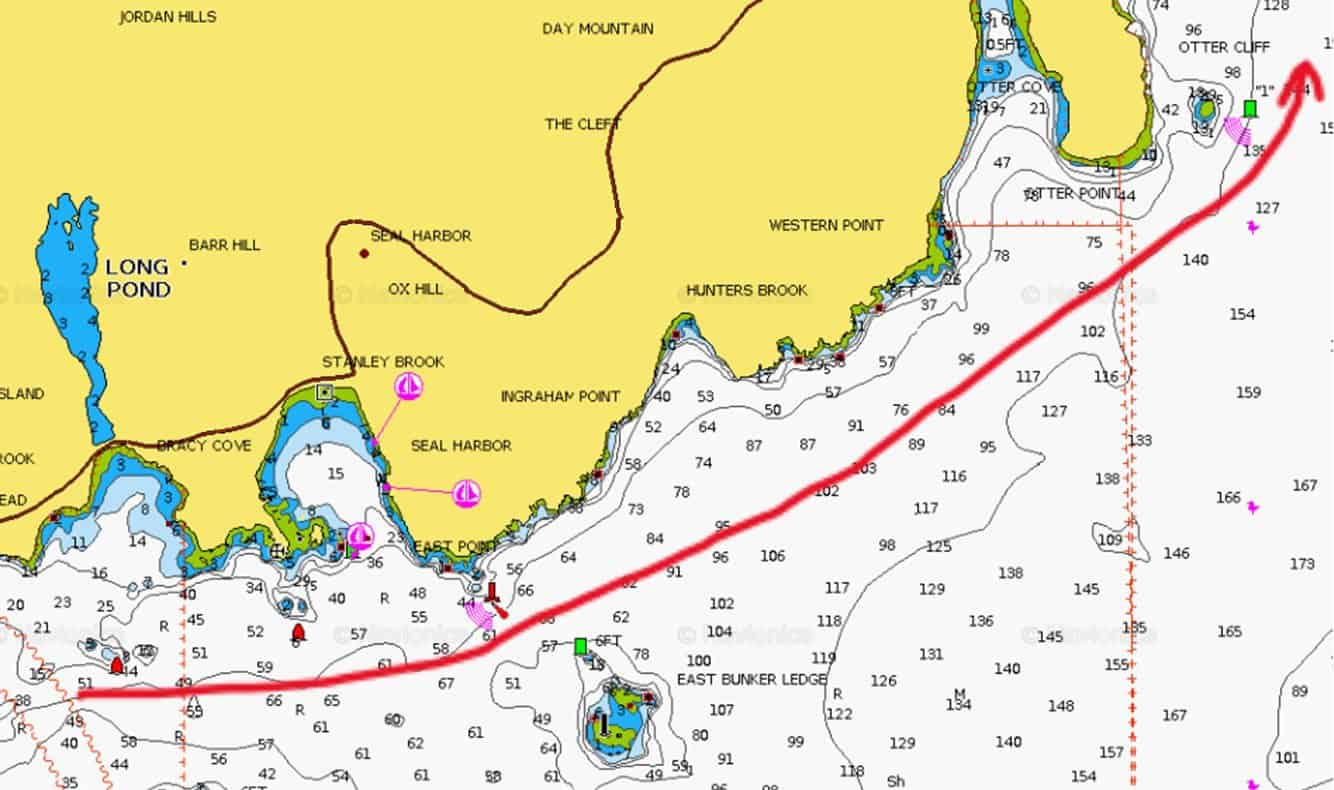

Above is a section of chart near Seal Harbor on Mt Desert Island. Northeast and Southwest Harbors lie off to the left (west) and Bar Harbor lies north on the other side of the island off the top right of the chart. If you were making a passage from either Northeast or Southwest Harbor to Bar Harbor you would be going east along the bottom of the chart and then turning north toward Bar Harbor. When passing by Seal Harbor you would keep three red marks (two nuns and a lighted bell buoy) to port and a green can marking East Bunker Ledge to starboard. As you begin to turn north and head toward Otter Cliff you see another green mark. This one, however, is to be left to port. Two green marks, one visible from the other, to be passed on opposite sides illustrate the point perfectly. The solution is always to study your charts and determine what the navigational aid is marking before you determine on which side to pass.

Tides – Depth and Current

Depth

The tidal range (i.e., the change in depth between low tide and high tide) is greater in Maine than anywhere else along the east coast. Tidal range increases as you proceed northeast along the coast, from 8.7 feet in Kittery to 18.4 feet in Eastport. The tidal range increases with the new and full moon phases to create spring tides that are 10 to 15% larger than the mean range.

Tides in Maine are semi-diurnal, meaning there are two highs and two lows in a 24-hour period. Actually, the period for two full cycles is approximately 25 hours, so that if you have a 7 AM high on Monday, on Tuesday the morning high will be at approximately 8 AM.

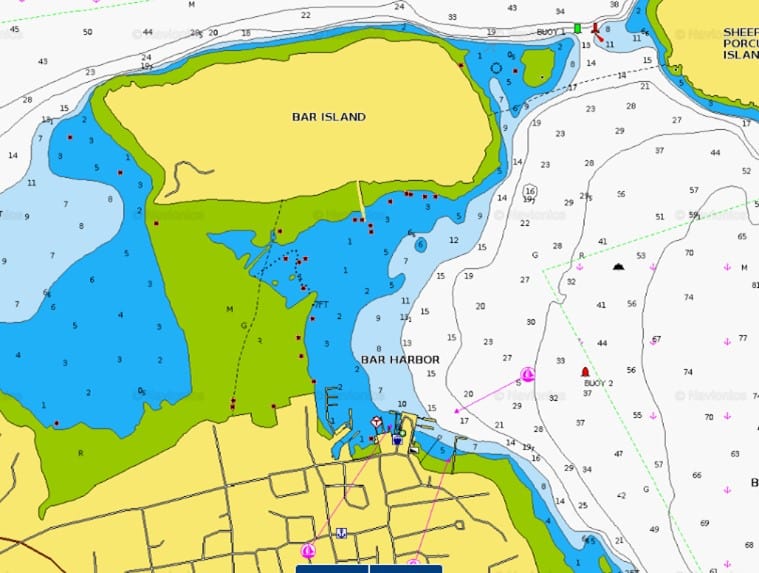

This time lapse video by Thomas Vispisiano is a very good illustration of the effect of the tide. Taken from the shore in the town of Bar Harbor looking across to Bar Island, it shows an ebb tide uncovering the sand bar that connects the two islands at low tide. What looks like a navigable stretch of water at high is, of course, not so, unless you are in your dinghy. The navigation hazard is quite evident on your chart. How many skippers do you suppose have fetched up on that sandbar because they came into the harbor at high tide and were not paying attention to their chart?

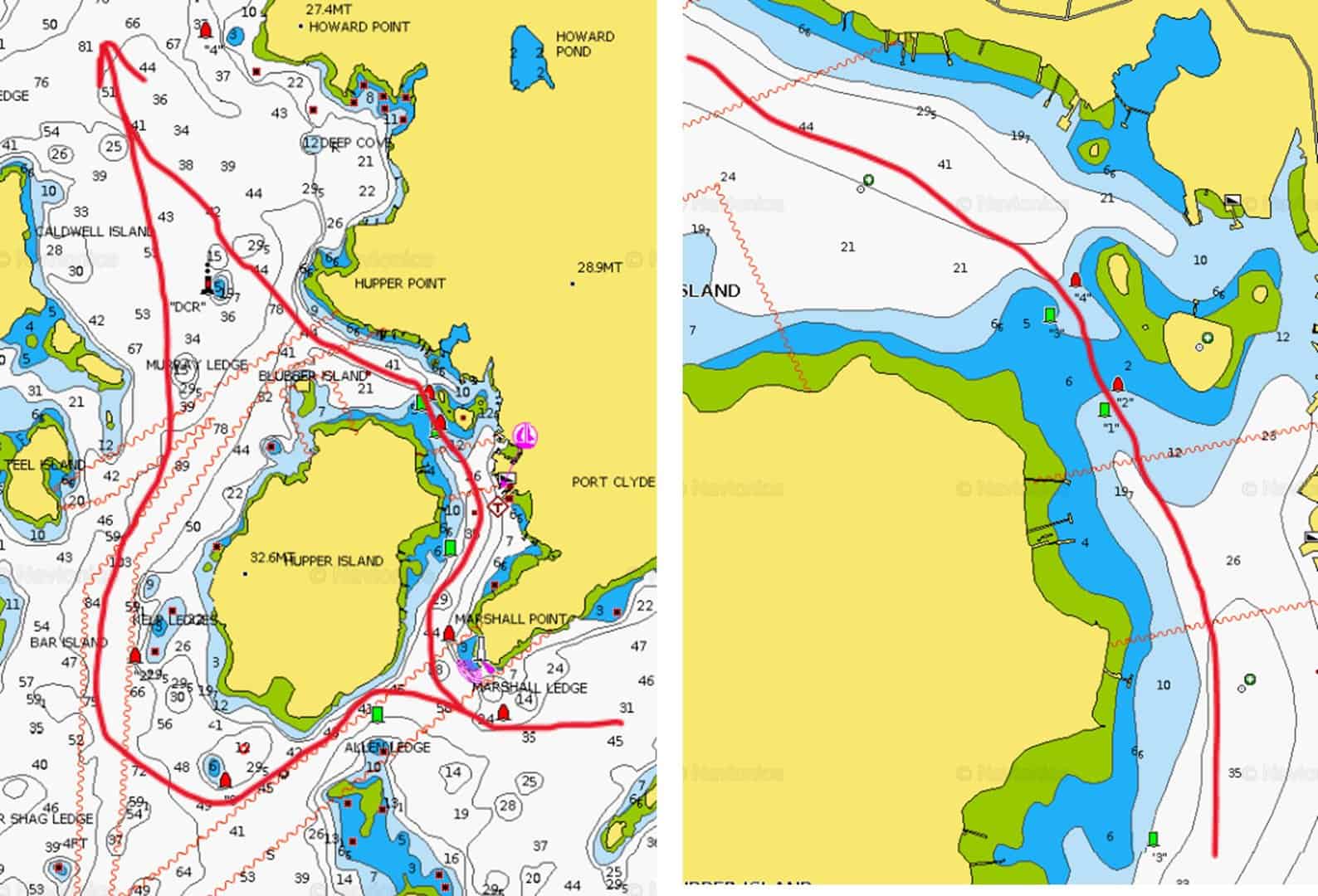

Here is an example of how awareness of the tide can save you time and distance. My wife, Meg, and I were returning from Penobscot Bay and planned to spend the evening in Maple Juice Cove, a peaceful anchorage on the west side of the St George River. We had two options for getting past Port Clyde and into the river with our sailboat, which draws 6’. The first was to loop around Hupper Island, which forms the western side of the harbor at Port Clyde. The second was to cut through Port Clyde and emerge into the river through the shallow but well-marked passage at the northern end of the harbor. The chart showed a minimum depth of 6 feet and a mud bottom through the passage. The tide was flooding, there was about two hours until high tide and it was a relatively calm day. The mean tidal range at Port Clyde is about 9.5’. We elected to try the shortcut and slowed down to 2 knots to pass through the channel. We never saw less than 11 feet of depth

I give this example only to demonstrate that the tides can affect your navigating decisions, not to suggest that you should seek to take risks with your choice of route. The best navigating decision is almost always the one that gives you the greatest margin for error and that you are comfortable with.

A second reason for being aware of the tide pertains to anchoring. We’ll cover the reasons for this in the section below on anchoring.

Current

There are few places in Maine where strong currents present a navigational hazard. The few spots that have notably strong currents would be Upper Hell Gate on the Sasanoa River, Lower Hell Gate in Knubble Bay, and some of the passages in the vicinity of Eastport. Strong current against an opposing wind can create steep waves and confused seas. This is not uncommon at the mouth of the Kennebec in the vicinity of Seguin Island.

Even modest current did play a bigger factor in navigation in the days before chartplotters and GPS, but it is quite easy these days to stay on course through the proper use of your chartplotter and instruments. Current is a consideration in anchoring (see the section below on Anchoring) and can also be a factor approaching docks or moorings and is definitely a factor in avoiding lobster buoys (see the section on lobster buoys below).

Fog

Clear skies and good visibility are the norm during the Maine summer. However, fog happens. With a bit of luck, you might not encounter any fog on your Maine cruise. But in some weather patterns it can persist for days or weeks (e.g., May and June in 2023 ☹). So, you must be prepared to deal with it. Fortunately, these days we have more tools at our disposal for navigating in reduced visibility than ever before. Here are a few tips for dealing with fog when you are cruising.

If you do make a passage:

- Treat your itinerary as a guide, not a mandate. Though not always possible, sometimes the best way to deal with fog is to stay put.

- Be patient. Morning fog often “burns off” when temperatures rise. Weather forecasts can offer some insight into weather that is likely, though fog forecasts tend to be less reliable than other parts of the forecast.

- Shorten your passage or alter it to avoid navigation challenges.

- If you venture out into the fog and decide you are not comfortable, don’t be afraid to return to port.

- It goes without saying that if you have radar, this is the time to use it. If you don’t have it, look for a buddy vessel with radar going the same way as you and follow them.

- AIS is a useful tool in fog. If you don’t have it on your vessel, consider getting it. It makes you visible to others who are monitoring AIS and allows you to track others with AIS. Set up your chartplotter to display AIS targets and consider setting AIS target alarms. Be aware however, that not every boat has AIS, and not all who do have it operating or are monitoring AIS traffic. Lobstermen (and women), of which there are many along the coast, tend not to use AIS and because they are busy working and may want to keep their location secret, but they do have radar and they generally keep an eye out for cruisers, but don’t depend on it.

- As you will be paying heightened attention to your plotter, a second or third set of eyes and ears on deck is highly recommended. When you have one or more lookouts, consider assigning them to different sides of your vessel. Bottom line, one person navigating, one person watching for pots. Helmsperson should always be aware of where the safe water is if a sudden course adjustment is required.

- Have a horn at the ready. A 4- to 6-second blast followed by two short 1- to 2-second blasts every 1 to 2 minutes is the recommended horn use procedure in fog.

- Maine has many rivers and bays that allow passage well inland. Cruising up these rivers and bays will often give you a complete and sunny respite from fog.

- Listening for horn blasts, engine noises and sometimes voices, is very important in fog. It is often the only way you will be aware of other boats if you lack radar and AIS capabilities.

- Being enveloped in thick fog can be highly disorienting. The only way you are likely to be able to keep track of where you are and in which direction you are heading is by using your chartplotter. Practice using it on a clear day!

- Slow down; fewer RPMs if you are motoring and a reduced sail plan if sailing. On some boats however, speed is safety as the lobster gear will deflect off the keel and rudder.

- Have your routing bring you near navigation marks or other points that will give you a confirming visual reference.

Weather

Temperatures

Typical summer (June-August) weather features high temperatures in the high-70s and lows in the high-50s (Fahrenheit). Foul weather, often accompanied by rain and SE winds, brings significantly cooler highs, in the 50s/60s. Water temperatures in July/August are in the mid-60s along the southern coast, decreasing as you proceed down east to the mid- to low-50s east of Mt Desert. Although there are many days when a t-shirt and shorts are perfectly comfortable attire, you should be prepared for the cooler weather. Good foul weather gear, fleece, a warm hat, and gloves are a must. Sailing at night in Maine can be very cold and damp and often requires that you dress as if to go skiing.

Winds

The typical wind pattern in the summer is for calm nights and a S to SW sea breeze during the day. The sea breeze is generated by a thermal gradient between the warm land and cooler offshore waters. The sea breeze develops gradually during the morning as the land heats up with the first zephyrs appearing as you approach noon and increases during the afternoon, perhaps to peak gusts of 20 knots. Sea breezes tend not develop on cloudy days or when the thermal gradient cannot overcome a synoptic wind. You might also notice a land breeze from the N to NW in the morning; if you ride that breeze (perhaps offshore) you might encounter a transition to a sea breeze, which may allow you to get west.

As noted above foul weather is usually accompanied by SE winds generated by lows passing to the south. There is no general rule about the strength of these winds, though they can very strong particularly early (May) and late (October) in the season.

Occasionally you will experience a NW wind, usually accompanied by cooler temperatures. These are more common in September and October and are a sign of the changing season. NW winds are typically gustier and shiftier than winds from the S as they have travelled over land before reaching you.

The best sources of wind forecasts are available for free on apps such as Windy or PredictWind. Local weather forecasts and offshore marine forecasts are not very good at predicting near-shore wind conditions.

Lobster Buoys

Getting snagged on a lobster buoy can ruin a good day of sailing, and in some places lobster buoys can be thick on the surface. Below, I’ll offer some suggestions for avoiding them and what to do if you do get snagged. First, it is useful to understand how the buoys function.

Maine lobstermen frequently set their traps in “strings” of 6-10 traps, each trap tied to another about 10 yards apart with line (called “warp”) and each of the end traps connected by warp to a buoy that floats on the surface. Each lobsterman’s buoys have a unique color scheme that identifies the string of traps as his. In some areas of the coast there are two buoys on the surface marking each end of the string, with the warp coming to the surface connecting to a buoy without a handle and the connected to a second handled buoy with the 20-foot length of warp that sinks below the surface between the two buoys. This method of marking string ends is used in areas of higher current as a single buoy set-up can be dragged under water by the current, whereas in a two-buoy set-up, the first buoy may get dragged under water, but the second buoy will remain on the surface. The two buoy set-ups usually, but not always, share a color scheme which allows you to identify buoys that are paired at the surface. The two-buoy rigs are more common from East Penobscot Bay and east from there.

The likelihood that you will be caught on a lobster buoy is also dependent on the design of your vessel. Full-keeled sailboats are somewhat less likely to be snagged than a fin keel or fin with a forward bulb. Now on to some suggestions.

- Vigilance is key and the denser the buoys, the more vigilance is required.

- A crewmate on deck keeping an eye-out can be very helpful. It can be helpful for you and your spotter to pay attention to different sides of the vessel, particularly if visibility is blocked by your sail plan.

- If you are in an area of the coast where the lobstermen are using two buoys—a primary buoy and a toggle buoy—try to identify the paired buoys and don’t go between them.

- Be aware of the effects of current and leeway on your direction of travel, but more importantly, which way the tide is setting the lobster gear. If the tide is setting the gear from left to right, always try to pass to the right of the buoy or if there is a second buoy (toggle) to the right of that.

- If you are motoring and you realize at the last minute that you are about to pass over a buoy, take your engine out of gear until you pass. The worst possible situation is to get the warp wrapped around your propeller. (Another option, depending on your keel and rudder configuration, is to increase the throttle to reduce the chance of getting caught!)

- If you get snagged while sailing you can usually free yourself by tacking, gybing or backwinding the main in order to back down.

- Shaft line and weed cutters are very effective. Shaft Razor and Shaft Shark will almost always rid your prop and shaft of line and other floating debris.

- If the warp gets wrapped around your prop, you can attempt to remove the warp (while in neutral) without cutting or diving. If that isn’t possible you can cut the warp, but the prop wrap may still prevent you from using the motor. In that case you need to be prepared to set the anchor or use the sails to proceed. Some experienced cruisers carry a hook knife placed on the end of a boat hook to have a swim-free escape.

- Finally, in some cases the only way to get a wrap off a prop is to dive under the boat with a sharp knife. You may or may not be comfortable with this, especially in cold Maine waters, so carrying at least a shorty wetsuit is strongly recommended Sometimes the only resort is to seek assistance for getting into port where you can find a diver or other help.

Anchoring

To fully enjoy cruising in Maine, you may want to spend most nights away from the busy harbors and in the many secluded anchorages. It is in these places where the magic of the Maine coast is most fully apparent. Below are a few tips for anchoring during a Maine cruise. I’m assuming that you are well-practiced in anchoring your vessel. If this is not the case, I highly recommend both training and practice before you commence your cruise.

- You should consult one or more cruising guides to choose a spot to anchor. The guides will give you lots of information: protection from wind and waves, hazards to navigation, nature of the bottom in the anchorage, etc.). If you have an itinerary that you are following, you’ll want to confirm each day that the destination you have chosen will be comfortable and safe given the predicted weather conditions.

- Factor the tide into how much chain / rode you put out. If you anchor with 6-1 scope in 10’ of water at low tide in an area with a tidal range of 10’, then at high tide your scope will be reduced to 3-1.

- Some anchorages may be crowded (even with only a few other boats at anchor). Choose a spot where you can anchor safely without impacting neighboring boats.

- The most prevalent bottom in Maine is mud. This will provide excellent holding. There are a few anchorages where the bottom is less conducive to good holding and usually the cruising guides will note this. Extra caution is advised in these places.

- Pay attention to your chartplotter when you choose an anchoring location. Make sure you are not anchoring over or near rocks that will be at or near the surface as the tide ebbs.

- When the wind dies at night, you may swing 180 degrees with the tide. If there is lobster gear within that circle make a note of the color of the buoy so that you can find it before departing in the morning. It might be hiding under your boat!

- Set an anchor alarm.

- Many anchorages offer the opportunity to take your dinghy to the shore for exploration on foot. Consult your cruising guide and always be respectful of private and protected land

All cruising areas have unique challenges as well as unique attractions. Maine’s coast will reward your attentive navigation with an unforgettable cruising experience second to none.