In calm water, at slack tide, in daylight, lobster pot buoys and their warps present only a moderate problem. The buoys and toggles are easy to see, and the warps drop straight down from the buoy or toggle, so steering around them is easy, even if you pass close aboard. You still must keep a sharp lookout, but usually, even if you hit the buoy dead on, your boat will slither on by without incident.

However, there is usually a tidal current in Maine, which means that the buoy is down-current of the trap, and the warp descends at an angle. If you come too close to the buoy on the up-current side, the diagonal line will pass under the keel and may catch on your keel, rudder (unless it’s attached directly to the keel), or propeller, even if it is not rotating. If the warp has only one buoy, it is usually easy to pass safely on the down-current side of it. So a basic rule is to observe how the buoys lie in the current constantly.

One of our readers suggested: "Also, you have to pay attention to where the stick is pointing--that’s the big trick. No matter how crowded it is, you just make sure that you are nearly rubbing the stick side. It points you where to go." More often than not these days, however, the conventional lobster buoy made of foam with a stick protruding from the top has been replaced by a molded hardshell buoy that very often will not have an appendage, so one needs to pass on the rounded end, not the end with the rope.

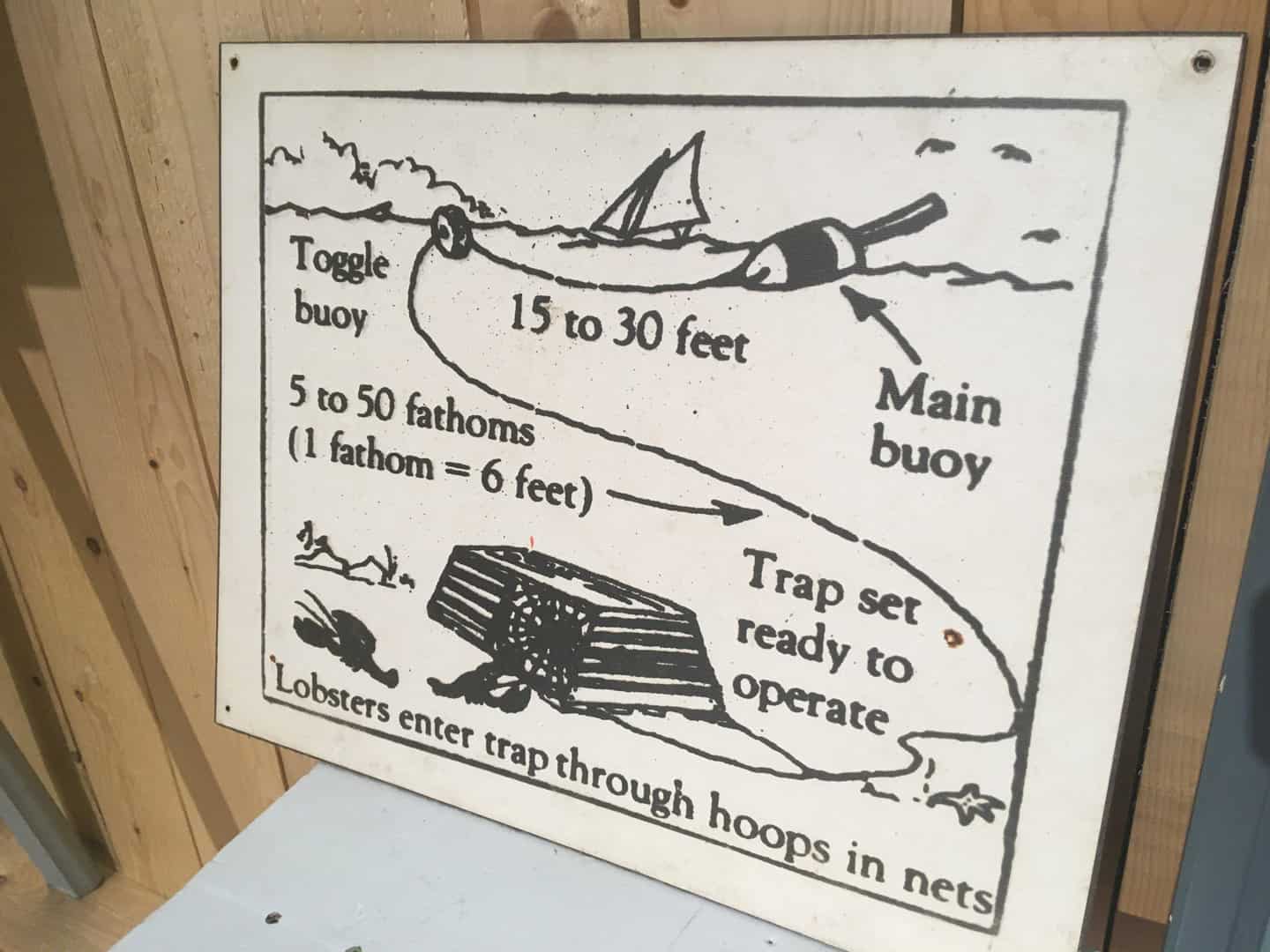

In some areas and water depths, there may be two buoys: one that suspends the warp that leads to the trap on the bottom, and another attached to the warp below the other buoy on a line of 20-30 feet that floats even farther down-current. The line between the two buoys sags below the surface – waiting to catch your keel, rudder, or propeller. It is therefore imperative NOT to go between the two buoys. Steer either downstream of the downstream buoy or WELL up-current of the up-current buoy – and don’t forget that you may be set rapidly down-current. In most areas, the buoy that suspends the warp is a small, often dark-colored cylinder (a “toggle”), and, in a strong current, it may be partly or entirely below the surface. In that case, the other buoy will be lying serenely and distinctively on its side. If the primary (often brightly-colored) buoy is alternately lying on its side and then popping upright as a wave passes, it is the one suspending the warp from the bottom – and there may be a toggle downstream of it.

The configuration of buoys and lines varies considerably by region, water depth, and fisherman. (If you want to know about the deployment of lobster traps and associated gear, by region: bycatch.org/sites/default/files/Lobster_Gear_Report_0.pdf)

If your propeller is engaged and you cannot avoid a buoy, take the engine out of gear – pronto!

The challenge of avoiding buoys is greater in fog and prohibitive in the dark.

When anchoring or picking up a mooring, note any buoys within your swinging circle. In the morning, locate each buoy, walk around your boat -- look carefully, especially under the counter and around the rudder. If necessary, get in the dinghy to ensure that you haven’t snagged a buoy during the night. You might even put a note on the binnacle to "find the green and orange buoy" before getting underway.

Extricating Yourself

A sure sign that you hit a warp is that its buoy starts to follow the boat. Or the boat slows almost to a stop, down-current of the trap and usually stern to the wind. If the propeller was turning, the engine likely stopped. Looking over the stern, you will probably see the warp stretched astern, although it may be five feet or more underwater.

Consider the risk to the boat: if you are in open water, you may be able to attend to extricating yourself; if not, you may need to consider anchoring or even calling for help.

Reduce sail. Do not engage the propeller.

If the warp caught on the keel, rudder, or stopped propeller, it may come off by itself as the warp becomes taught.

If you are still stuck after five minutes, it’s time to get in the dinghy – firmly attached to the boat and with the oars in the dinghy - and investigate. With some luck, you may be able to see the buoy hooked around the rudder or propeller and free it with a boat hook. Failing that, you may be able to pull the warp to the surface and cut it – but bear in mind that its owner may then lose $200-300 worth of gear and future income from lost traps (not to mention the lobsters that will end their days in the abandoned trap). You will still need to remove the buoy and remaining line from the keel, rudder, or propeller. And, if the propeller is fouled, you may not be able to use the engine.

Nearby lobstermen may come to your aid, not just to kindly help you but to avoid the loss of their fellow fisherman’s gear. Often, they can free you and also save the gear.

If you are still stuck, it’s time to consider swimming under the boat. Important considerations are: how capable you are of swimming down five feet or so and working underwater for 15-30 seconds, likely multiple times; the temperature of the water; whether you have a wetsuit and preferably a mask; how much current you are in that may make the job difficult or impossible and when the tide will turn; how much wind will propel the boat through the water if you are successful and how you will get back onboard a moving boat. Always tether yourself to the boat forward of the boarding ladder, stop the engine, and have a plan for what the crew will do if you are successful, e.g., helping you back aboard and controlling the boat.

My friend, Jim Starkey of Manchester YC, adds “A trick we have learned, not as good as avoiding them, but almost, is to pull enough warp to cleat some excess, taking the strain off whatever is stuck below, making it much easier to disentangle.”

Suggested Equipment: Keep an inexpensive (sharp) basic fisherman's knife in a protective sheath attached to your stern pulpit or backstay. Have handy a telescoping boat hook to which you quickly attach the knife using that most essential bit of boat gear, duct tape!

CCA member Ernest Hamilton suggests carrying an anvil ratchet hand pruner such as a Fiskars P973 for cutting lines off the prop.

Finally, many cruisers rely on a cutting blade mounted on the propeller shaft such as the Shaft Shark. It is very effective.

Otherwise, you may be able to call for assistance from the Coast Guard or a commercial towing or diving service.

CCA Member Nat Warren White tells this story of his recent encounter with pot buoys: It was only last summer as I was motor sailing through the Muscle Ridge Channel that I picked up my most recent victim. I didn’t even know I’d snagged it until the shaft seized. It had been dragged under by the current, so was totally invisible. I had been under power but was just hoisting sails when we got snagged. I saw pieces of the buoy spit out astern, so I knew we’d cut it with the cutter, but I still had line wrapped on the shaft and prop. I was able to continue sailing, fortunately, because we were in a tight part of the channel. It was impossible to get the engine out of gear, so I just shut it down. When we sailed into Tenant’s Harbor, there was not much breeze, so I could grab a mooring easily and then donned my shorty wetsuit, mask and flippers and attempted to dive with a sharp knife to clear things. Sadly, the pot warp was wound so tight it had burned into the cutlass bearing. There was no way I could clear it with the short amount of breath I managed to hold between dives. After a dozen or so attempts, I gave up and called the boatyard. They told me there was a local diver who might be able to help. He showed up an hour later in a dinghy, all geared up and ready to go to work. He explained that he was a lobsterman who had just finished hauling. I apologized and said I hoped it wasn’t his gear I had cut. He laughed and said, “No worries. It’s an occupational hazard.” I was relieved and grateful and not at all resentful of the $100 he charged me, especially since he offered to check my zincs and thru-hulls while he was down there. We had a nice visit and he did a good job fixing us up. Just one more day in the life of a Maine cruiser!