As marinas in Maine are somewhat sparse, and the anchoring opportunities are plentiful and fabulous, anchoring is a valuable skill set to possess while cruising Maine.

General observations for anchoring anywhere from Maine to the Caribbean:

- The attraction of a tight, snug anchorage is undeniable. Privacy, good protection from wind and waves, tranquil beauty are all attributes that cruisers seek. But always consider that the lack of breeze and the proximity to the shore and trees could convert that idyllic retreat into a bad dream should mosquitos and other hungry species decide to share your space. Also, if the weather is hot, the lack of breeze will be a big negative.

- If it looks too good to be true, it probably is. You arrive at your desired anchorage and find that while it’s crowded, there’s a beautiful spot that’s empty. You hustle over there and claim your piece of paradise. Soon you discover, however, that the reason for the perfect spot being empty is that the bottom is rocky or hardpan or covered in kelp and that’s why it’s available.

- When you find your desired anchoring location, circle your drop site first to check the actual depth versus the charted depth and to confirm that you have adequate swing room. When searching for a good anchoring spot in Falmouth, Antigua, I spotted an open area that qualified for “too good to be true” status—the charted depth showed 7 feet, my draft was 6’ 2”, but I made two very cautious (slow) circles with a decreasing radius and discovered that there was actually 9 feet of depth. Perfect! Stayed there a week. Caution works both ways!

- Go with your gut. If an anchoring location doesn’t feel right for any reason or even if you can’t put your finger on the reason, trust your instincts and try someplace else. We’ve done this dozens of times and slept better for it.

- When approaching a proposed anchorage, start thinking of and communicating all of the variables that need to be considered. Target depth, proposed proximity to other boats or obstructions, and get a weather forecast so that at 2 am when the wind pipes up from a new direction, you are set up properly and can stay in your bunk. How will the tide or current affect the direction of your set? When all these factors have been discussed, then agree upon the drop site, the amount of scope, and the heading while in reverse to pay out the scope. Hopefully you are fortunate to have a boat that will back to the right, left or straight so you can set with some directional precision.

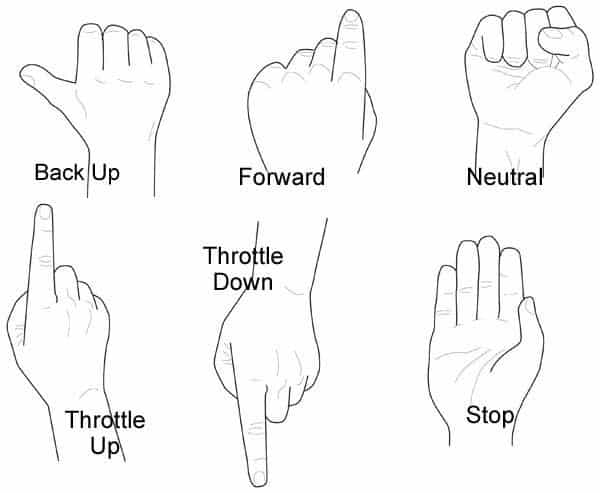

- Hand signals are essential as any amount of wind will make voice communication impossible. Our hand signals communicate: back down slow, fast or medium; go to neutral; dead stop; cut engine; heading direction; tell me the depth; confirm good set or abort and retrieve the anchor. Retrieving the anchor will have similar signals but will also include light forward throttle to break out anchor; speed and direction while retrieving the rode; drift for clean up; and all secure, proceed. Here’s a basic set of hand signals that might be a good starting point.

One last piece of advice from a couple that have been anchor “communicating” bow to stern for nearly fifty years: change roles occasionally and experience the challenges faced by the other half of the team. Trust me: it’s the solution to world peace.

- Rode (chain or rope) markers of any type are important. The only time I ever dragged in the Caribbean was because the rode markers had worn away and putting on the new ones never got to the top of the list. We had adjusted the scope several times to fit into a tight spot and, in the process, had reduced scope to 1.5:1!

- Newer style anchors are better and well worth the money. We love our Manson, others love Rocna, Ultra, Mantus, and others. FMI: Practical Sailor, Happy Hooking: The Art of Anchoring by Alex and Daria Blackwell, Attainable Adventure Cruising by John Harries and Phyllis Nickel.

- The great debate: What’s the best rode? We probably have an equal number of miles using a chain/rope combination as with a mostly chain rode. We have had great success with both approaches. The advantages of a modest amount of chain (say 40 feet) are ease of handling if you don’t have a windlass, somewhat easier cleanup when anchoring in mud as rope doesn’t seem to collect as much mud as chain, and better sailing performance in a seaway due to reduced weight in the bow. The disadvantages include less catenary effect from less chain; potential chafe on the chock or a rough bottom; possible entanglement of keel or rudder in wind or current direction changes; longer scope requirements, so fewer opportunities in crowded areas; windlass difficulty in handling the rope-to-chain transition (splice), especially as the rode gets older and stiffer; and finally, less strength. We were on our second Caribbean winter cruise with 40 feet of chain, when after a sporty night of Christmas winds in the 30-knot range, I discovered our six-month-old, top of the line rope rode had completely unlaid!

The advantages of an all-chain rode (or at least 3- or 4-times your normal anchoring depth) are shorter scope—so more positioning flexibility, no chafe, no rope-to-chain transitions for the windlass, and significant peace of mind in a blow. Disadvantages include a bigger clean-up job when anchoring in mud, more weight in the bow, a windlass requirement (more cost, more complexity and still more weight in the bow) and a phenomenon I call “welding the pile.” What’s welding the pile? Go to weather offshore in 20 to 30 knots for a few days, and you may find that your pile of chain has settled into a very compact and almost solid lump from which it is seemingly impossible to deploy the chain. If you like passionate cocktail hour discussions, raise the topic of anchors and rodes. You’ll get an earful!

What makes anchoring in Maine unique?

- Maine has hundreds of scenic coves and harbors where one can really appreciate the exceptional beauty of the coast, and better yet, it’s free! After all, marinas in Maine are relatively scarce, expensive, and crowded in prime cruising season.

- You will almost always be rewarded by delaying your departure until the sea breeze fills in after lunch—but that also means that you are liable to be a relatively late arrival in a popular anchorage hence facing a reduced number of anchoring options. There’s the dilemma, but the crowd factor is nothing like what is encountered in southern New England. Rest assured there are many, many anchorages that are not crowded. This guide features just such places.

- Holding ground in Maine is primarily mud, which is good for minimizing the chances of dragging. As tenacious as the mud is in keeping you in one spot, it is also persistent in adhering to your anchor and rode. A good wash-down pump is invaluable. You may occasionally encounter kelp, rocky or gravel bottoms, or detritus on the bottom, but not often.

- You may encounter lobster pots where you intend to anchor. These areas are best avoided for several reasons. One is that as your boat goes up and down with the tide, or changes direction with the wind or current, you may become entangled in the lobster gear. Or the pot buoy may start bouncing off the hull in the middle of the night. If there is lobster gear nearby and you think you are okay, make a note to look for that green and yellow pot buoy that was just off your stern last night and locate it before getting underway the following day.

- Remember that the rise and fall of the tide in Maine is 8 to 15 feet, depending on local conditions. Take this into account when calculating scope and swing room. Also, be aware that in some areas the current will reverse direction every six hours, or in combination with the wind, you may find yourself going in circles! In the days of cruising with a rope and chain rode, we have more than once found the rode wrapped around the keel…. now that’s fun!

In summation, Maine is one of the best places on earth to anchor. There are hundreds of gorgeous harbors, coves, and creeks, a great many with excellent holding and generally lots of swing room and privacy.